- For the film and television narrative technique, see Cutaway (filmmaking).

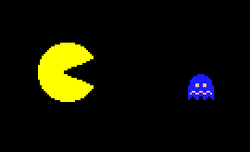

The cutscene in the original Pac-Man game exaggerated the effect of the power pellet power-up[1]

A cutscene or event scene (sometimes in-game cinematic or in-game movie) is a sequence in a video game over which the player has no or only limited control, breaking up the gameplay and used to advance the plot, strengthen the main character's development, introduces enemy characters, and provide background information, atmosphere, dialogue, and clues. Cutscenes often feature on the fly rendering, using the gameplay graphics to create scripted events. Cutscenes can also be animated, live action, or pre-rendered computer graphics streamed from a video file. Pre-made videos used in video games (either during cutscenes or during the gameplay itself) are referred to as "full motion videos" or "FMVs".

History[]

In 1983, the laserdisc video game Bega's Battle introduced the use of animated full-motion video (FMV) cut scenes with voice acting to develop a story between the game's shooting stages, which would become the standard approach to video game storytelling years later.[2] The 1984 game Karateka helped introduce the use of cut scenes to home computers. Other early video games known to make use of cut scenes as an extensive and integral part of the game include Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken in 1983; Valis in 1986; Phantasy Star, Maniac Mansion and La Abadía del Crimen in 1987; Ys II: Ancient Ys Vanished – The Final Chapter, and Prince of Persia and Zero Wing in 1989, with the poor translation in Zero Wing's opening cutscene giving rise to the (in)famous Internet meme "All your base are belong to us" in the 2000s. Since then, cutscenes have been part of many video games, especially in action-adventure and role-playing video games.

Types[]

Live-action cutscenes[]

Screenshot of a live-action cutscene from Command and Conquer: Red Alert

Live-action cutscenes have many similarities to films. For example, the cutscenes in Wing Commander IV utilised both fully constructed sets, and well known actors such as Mark Hamill and Malcolm McDowell for the portrayal of characters.

Some movie tie-in games, such as Electronic Arts' The Lord of the Rings and Star Wars games, have also extensively used film footage and other assets from the film production in their cutscenes. Another movie tie-in, Enter the Matrix, used film footage shot concurrently with The Matrix Reloaded that was also directed by the film's directors, the Wachowskis.

Some gamers prize live-action cutscenes for their kitsch appeal, as they often feature poor production values and sub-standard acting. The cutscenes in the Command & Conquer series of real-time strategy games are particularly noted for often hammy acting performances.

Live action cutscenes were popular in the early to mid 1990s with the onset of the CD-ROM and subsequent extra storage space available. This also led to the development of the so-called interactive movie, which featured hours of live-action footage while sacrificing interactivity and complex gameplay.

Increasing graphics quality, cost, critical backlash, and artistic need to integrate cutscenes better with gameplay graphics soon led to the increased popularity in animated cutscenes in the late 1990s. However, for cinematic effect, some games still utilize live-action cutscenes—an example of this is Black, which features interviews between main character Jack Kellar and his interrogator filmed with real actors.

Animated cutscenes[]

There are two primary techniques for animating cutscenes.

Like live-action shoots, pre-rendered cutscenes are also part of full motion video. Pre-rendered cutscenes are animated and rendered by the game's developers, and are able to take advantage of the full array of techniques of CGI, cel animation or graphic novel-style panel art. The Final Fantasy series of video games, developed by Square Enix, are noted for their prerendered cutscenes, which were introduced in Final Fantasy VII. Blizzard Entertainment is also a notable player in the field, with the company having a department created especially for making cinema-quality pre-rendered cutscenes, for games such as Diablo II and Warcraft III.

Screenshot of a pre-rendered cutscene from Warzone 2100, the free and open-source video game

In 1996 Dreamworks created The Neverhood, the only game to ever feature all-plasticine, stop-motion animated cutscene sequences. Pre-rendered cutscenes are generally of higher visual quality than in-game cutscenes, but have two disadvantages: the difference in quality can sometimes create difficulties of recognizing the high-quality images from the cutscene when the player has been used to the lower-quality images from the game; also, the pre-rendered cutscene cannot adapt to the state of the game: for example, by showing different items of clothing worn by a character. This is seen in the PlayStation 2 version of Resident Evil 4, where in cutscenes, Leon is seen always in his default costume because of processor constraints that were not seen in the GameCube version.

In-game cutscenes are rendered on-the-fly using the same game engine as the graphics in the game proper, this technique which is also known as Machinima. These are frequently used in the RPG genre, as well as in the Metal Gear Solid, Grand Theft Auto (both games making use motion capture), and The Legend of Zelda series of games, among many others. In newer games, which can take advantage of sophisticated programming techniques and more powerful processors, in-game cutscenes are rendered on the fly and can be closely integrated with the gameplay. Some games, for instance, give the player some control over camera movement during cutscenes, for example Dungeon Siege, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, Halo: Reach, and Kane & Lynch: Dead Men.

Games such as Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos have used both pre-rendered (for the beginning and end of a campaign) and the in-game engine (for level briefings and character dialogue during a mission).

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when most 3D game engines had pre-calculated/fixed Lightmaps and texture mapping, developers often turned to pre-rendered graphics which had a much higher level of realism. However this has lost favor in recent years, as advances in consumer PC and video game graphics have enabled the use of the game's own engine to render these cinematics. For instance, the id Tech 4 engine used in Doom 3 allowed bump mapping and dynamic Per-pixel lighting, previously only found in pre-rendered videos.

Interactive cutscenes[]

Interactive cutscenes involve the computer taking control of the player character while prompts (such as a sequence of button presses) appear onscreen, requiring the player to follow them in order to continue or succeed at the action. This gameplay mechanic, commonly called quick time events, has its origins in interactive movie laserdisc video games such as Dragon's Lair, Road Blaster,[3] and Space Ace.[4]

No cutscenes[]

Template:Refimprove A recent trend in video games is to avoid cutscenes completely. In a technique popularized by Valve's 1998 video game, Half-Life, the player retains control of the character at all times, including during non-interactive scripted sequences, and the player character's face is never seen. This technique has since been used by a number of other games. Ubisoft's Assassin's Creed also allows the player to retain limited control over the character during the "cutscenes", though their movement is severely limited. This is meant to immerse the player more in the game, although it requires more effort on the part of the developer to make sure the player cannot interrupt the scripted actions that occur instead of cutscenes. Scripted sequences can also be used that provide the benefits of cutscenes without taking away the interactivity from the gameplay.

Director Steven Spielberg, an avid video gamer, has criticized the use of cutscenes in games, calling them intrusive, and feels making story flow naturally into the gameplay is a challenge for future game developers.[5]

See also[]

<templatestyles src="Div col/styles.css"/>

- Computer animation Template:Nb10

- Interactive movie

- Intro

- Machinima

- Outro

- Scripted sequence

References[]

- ↑ Matteson, Aaron. "Five Things We Learned From Pac-Man". http://joystickdivision.com. External link in

|publisher=(help)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles> "This cutscene furthers the plot by depicting a comically large Pac-Man". - ↑ Fahs, Travis (March 3, 2008). "The Lives and Deaths of the Interactive Movie". IGN. Retrieved 2011-03-11.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Rodgers, Scott (2010). Level Up!: The Guide to Great Video Game Design. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-470-68867-0.

- ↑ Mielke, James (2006-05-09). "Previews: Heavenly Sword". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

Some points in key battles (usually with bosses) integrate QTE (quick-time events), which fans of Shenmue and Indigo Prophecy might like, but which we've been doing since Dragon's Lair and Space Ace. Time to move on, gents.

<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles> - ↑ Chick, Tom (2008-12-08). "A Close Encounter with Steven Spielberg". Yahoo!. http://games.yahoo.com/blogs/plugged-in/where-did-video-games-152.html. Retrieved 2008-12-11.